I had already begun writing Twentymile, a thriller that takes place in and around Great Smoky Mountains National Park, when I learned I wasn’t alone in setting my crime novel in one of the U.S. national parks. In fact, Scott Graham has now released seven books in his National Park Mystery Series (published by Torrey House Press), each set in a different western park, from Yosemite to Arches to Grand Canyon. In addition, Christine Carbo has written four suspense novels all set within Glacier National Park. I discovered these fantastic books later, when I finally bothered to research whether there might be a market for the book I was laboring over. (Turns out, there just might be.) And while the idea for Twentymile may have arisen from the fallow field of my mind, I would never have completed it without Graham and Carbo showing me the way.

Many people have asked me along the way: Why write a crime story that occurs in what most readers would conceive of as an idyllic setting—one that conjures images of Smokey Bear, untouched forests, and childhood vacations in the wood-paneled station wagon? In truth, I asked myself the same thing any number of times while writing Twentymile. What was I thinking, sullying this nostalgic locale with such bloody goings-on? Would anyone even believe it? It was only through the process of finishing the novel that I arrived at answers to these questions.

First, let’s be clear about this: Crimes occur on public lands. These parks are often composed of large swathes of property, both rugged and remote, with a low density of humans when compared with urban and suburban areas. In other words, someone seeking to hide their nefarious activities could do much worse. In addition, the U.S. national parks alone (never mind national forests and wilderness areas, wildlife refuges, and state parks) had nearly two hundred million visits in 2020. Statistically, not all of those visitors could have been the greatest of people, and there’s no means of requiring them to check their criminal inclinations into a locker at the visitors’ center.

The moment I knew I had a novel idea with legs was when I came across an article in Outside Magazine entitled “The F.B.I. of the National Park Service.” This article introduced me to the little-known Investigative Services Branch of the Park Service—roughly three dozen special agents dedicated to investigating the most serious crimes committed on Park Service land. The ISB’s Special Agent in Charge of Operations, Christopher Smith, explained to me that, due to the small number of agents and the massive amount of territory under their jurisdiction, ISB special agents must be prepared to operate solo in some of the most remote areas in the country. Imagine no cell service, spotty GPS service, no readily available back-up, no forensics team to work scenes for you. What kind of person chooses that for their profession? What if something were to go badly wrong out there? What if, in the backcountry, a special agent were to encounter something or someone truly dangerous? As far as hooks for a novel go, I knew it was pretty good.

In addition, while national parks are now held up as “America’s Best Idea” (see the Ken Burns documentary series), the lands they occupy have difficult histories that aren’t discussed nearly enough. Put simply, it wasn’t always government land. How could it be? The United States of America isn’t even two hundred fifty years old. Which means someone else—perhaps even multiple groups over time—had it previously and then lost it. Case in point: virtually all of the parks sit on lands that historically were home to Indigenous people groups who no longer have the ability to occupy them under prevailing U.S. law. To some—and it is hard to argue with this conclusion—the parks are the product of theft.

In the 1820s, the five hundred thousand acres comprising Great Smoky Mountains National Park was part of the contracting Cherokee homeland. Had President Andrew Jackson not decided to ignore treaties with the Cherokee and forcibly removed them to Oklahoma, there would be no Great Smoky Mountains National Park. It’s as simple as that. After Removal, white settlers and timber companies moved in and occupied the land for a century, establishing farms and homesteads and clear-cutting forests. So striking was their misuse of the land that, in the 1920s and 1930s, the federal government employed a strategy to gather up as much as it could and oust the residents laying waste to it. While the displaced white settlers and businesses at least were paid fair market value for what they lost (the Cherokee, in contrast, were rounded up and marched away at gunpoint), still the government’s actions gave rise to anger and resentment that lingers in some to this day.

In addition to providing a solid motive for criminal activity, this history is fertile thematic soil. From it arise all manner of important questions. What does “home” actually mean, and what is the effect of its loss? What justifications do we as a country hold forth to support our appropriation of others’ homelands? And what do we owe to those from whom it was taken? (For one salient idea, see David Treuer’s compelling opinion piece “Return the National Parks to the Tribes,” in The Atlantic.) That kind of complexity is catnip to a novelist.

Finally, wild places add their own unique elements to a story that their urban counterparts arguably lack. There’s the beauty of the natural world, of course, and all that it has inspired in writers for centuries. I could go on for days about what it inspires in me. And the geographical and geological diversity of the national parks can hardly be rivaled. Added to this are the dangerous terrain and solitude they offer in their most remote corners, the threat that beauty can turn deadly in an instant. There’s a kind of storytelling alchemy that can occur when putting one’s character through that kind of ringer. As a writer, I and my characters find out together what they’re really made of, whether they’ll come out stronger on the other side.

Or if they’ll come out at all.

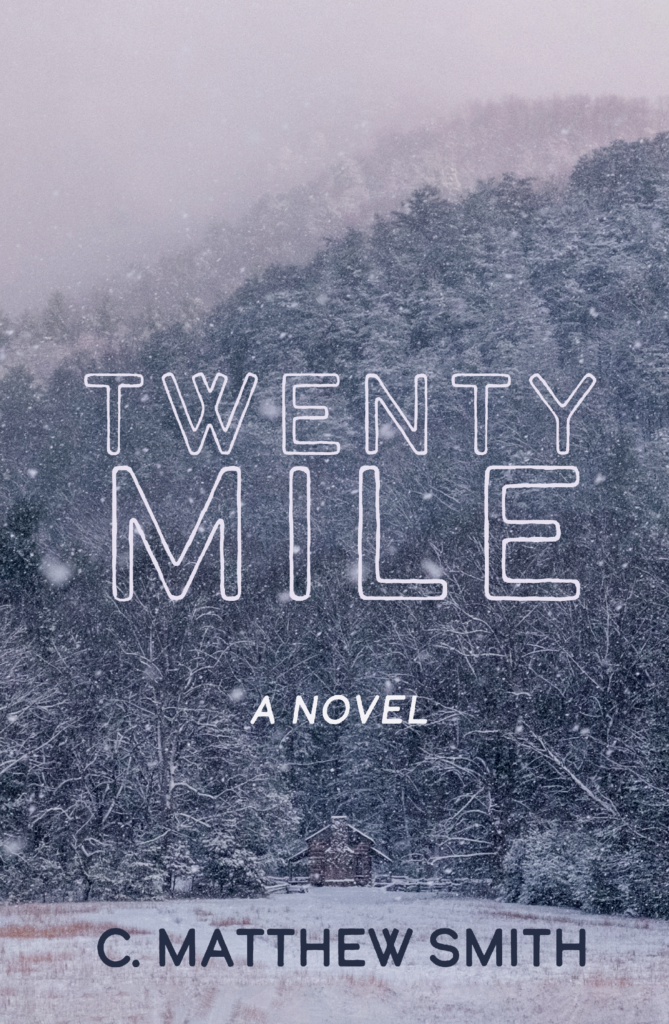

Publication Date: November 19, 2021

When wildlife biologist Alex Lowe is found dead inside Great Smoky Mountains National Park, it looks on the surface like a suicide. But Tsula Walker, Special Agent with the National Park Service’s Investigative Services Branch and a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, isn’t so sure.

When wildlife biologist Alex Lowe is found dead inside Great Smoky Mountains National Park, it looks on the surface like a suicide. But Tsula Walker, Special Agent with the National Park Service’s Investigative Services Branch and a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, isn’t so sure.

Tsula’s investigation will lead her deep into the park and face-to-face with a group of lethal men on a mission to reclaim a historic homestead. The encounter will irretrievably alter the lives of all involved and leave Tsula fighting for survival – not only from those who would do her harm, but from a looming winter storm that could prove just as deadly.

A finely crafted literary thriller, Twentymile delivers a propulsive story of long-held grievances, new hopes, and the contentious history of the land at its heart.

This is a Rafflecopter giveaway hosted by Partners in Crime Virtual Book Tours for C. Matthew Smith. There will be TWO winners. ONE (1) winner will receive (1) $25 Amazon.com Gift Card and ONE (1) winner will receive one (1) signed physical copy of Twentymile by C. Matthew Smith. The giveaway runs November 15 through December 12, 2021. Void where prohibited.

This is a Rafflecopter giveaway hosted by Partners in Crime Virtual Book Tours for C. Matthew Smith. There will be TWO winners. ONE (1) winner will receive (1) $25 Amazon.com Gift Card and ONE (1) winner will receive one (1) signed physical copy of Twentymile by C. Matthew Smith. The giveaway runs November 15 through December 12, 2021. Void where prohibited.

C. Matthew Smith is an attorney and writer whose short stories have appeared in and are forthcoming from numerous outlets, including Mystery Tribune, Mystery Weekly, Close to the Bone, and Mickey Finn: 21st Century Noir Vol. 3 (Down & Out Books). He’s a member of Sisters in Crime and the Atlanta Writers Club.

C. Matthew Smith is an attorney and writer whose short stories have appeared in and are forthcoming from numerous outlets, including Mystery Tribune, Mystery Weekly, Close to the Bone, and Mickey Finn: 21st Century Noir Vol. 3 (Down & Out Books). He’s a member of Sisters in Crime and the Atlanta Writers Club.

Great guest post! My mom lives in TN just north of the Smokies.

My husband and I owned a cabin in the Adirondacks for about 20 yrs. I would love to see you write a book set there! I would definitely read it! LOL

Sounds like a very interesting book!