In several courses I have taken on mystery writing, the instructor tries to dissect the genre. You know the outline already. The book opens with a dead body and then for the rest of the book someone in the role of detective or amateur detective tries to figure out who done it. We all love the mystery genre and we keep right on guessing, book after book.

In several courses I have taken on mystery writing, the instructor tries to dissect the genre. You know the outline already. The book opens with a dead body and then for the rest of the book someone in the role of detective or amateur detective tries to figure out who done it. We all love the mystery genre and we keep right on guessing, book after book.

I hold nothing against this formula. If a writer can write to expectations, and add one or two fresh twists or slants, that often makes for ideal reading. But I knew that wouldn’t work for the novel I had in mind, the novel that became The Murderess Must Die. I chose to write a novel based on a true crime, a crime where we know from the start who done it—Martha Place, a middle-aged woman living in Brooklyn in 1898. We know from the trial transcript how the police caught her and about the circumstantial evidence they collected. We know the jury found her guilty and we learn that the judge sentenced her to die in the electric chair in Sing Sing—the first woman to be executed in that manner. For most mysteries or procedurals, the reader learns details about the crime and investigation slowly, through clues, foreshadowing, maybe some red herrings. I followed a different path in writing my book, since anyone checking out Martha Place on Wikipedia would know her fate. I chose to open the novel with Martha telling us, from the grave, that she was convicted of first-degree murder.

“How can you write a mystery when the identity of the killer is clear on page one?” my so-called friends asked. Anticipating that question, I expanded the idea of what mystery means.

For novels, the most common interpretation of the word mystery centers around the identity of the killer. Instead, I explored the mystery of motivation. Before allegedly killing her stepdaughter, Martha Place had never committed any crime more serious than raising an occasional ruckus. Martha did not look slovenly. She was known for taking care with her clothes. She married a respectable man of means and lived in a nice row house in a prosperous neighborhood. During the period when she lived, many Americans carried the stereotype that crimes were committed by new immigrants, especially those from Eastern Europe. But my character was native-born, probably of Dutch descent. As we would say today, she did not fit the profile of a killer. I create suspense about her motivations, more than her guilt. I try to unwrap the layers of the onion, hinting at one possible provocation after another, building up to the point where the reader can imagine how this woman exploded with rage.

Besides the mystery of motivation, I introduce at least a modicum of mystery about whether the police caught the right person. We see Martha Place throwing acid in her stepdaughter’s face, we see her hitting her stepdaughter with the handle of an axe, and we come close to seeing her suffocate her stepdaughter with a pillow. But we don’t actually see that final deed. And it’s not clear that Martha, in her enraged state, knows exactly what she has done. She refuses to confess through months of questioning and imprisonment. I should add that she most likely was guilty, but neither reporters, nor police, nor the woman’s lawyers turned over every stone. In what may be the most fictional part of my story, I lay the ground for other possibilities. Even writers who take care to stay close to what is believable can find points to speculate.

I have told you how I created mysterious elements in a novel where the key mystery—who is the killer?—is not much of a mystery. These are simply my own variations on a theme. When you think mystery, have an expanded view of the concept. You probably have mysteries in your own life—certainly aspects of your biography that are mysteries to others and maybe even to yourself.

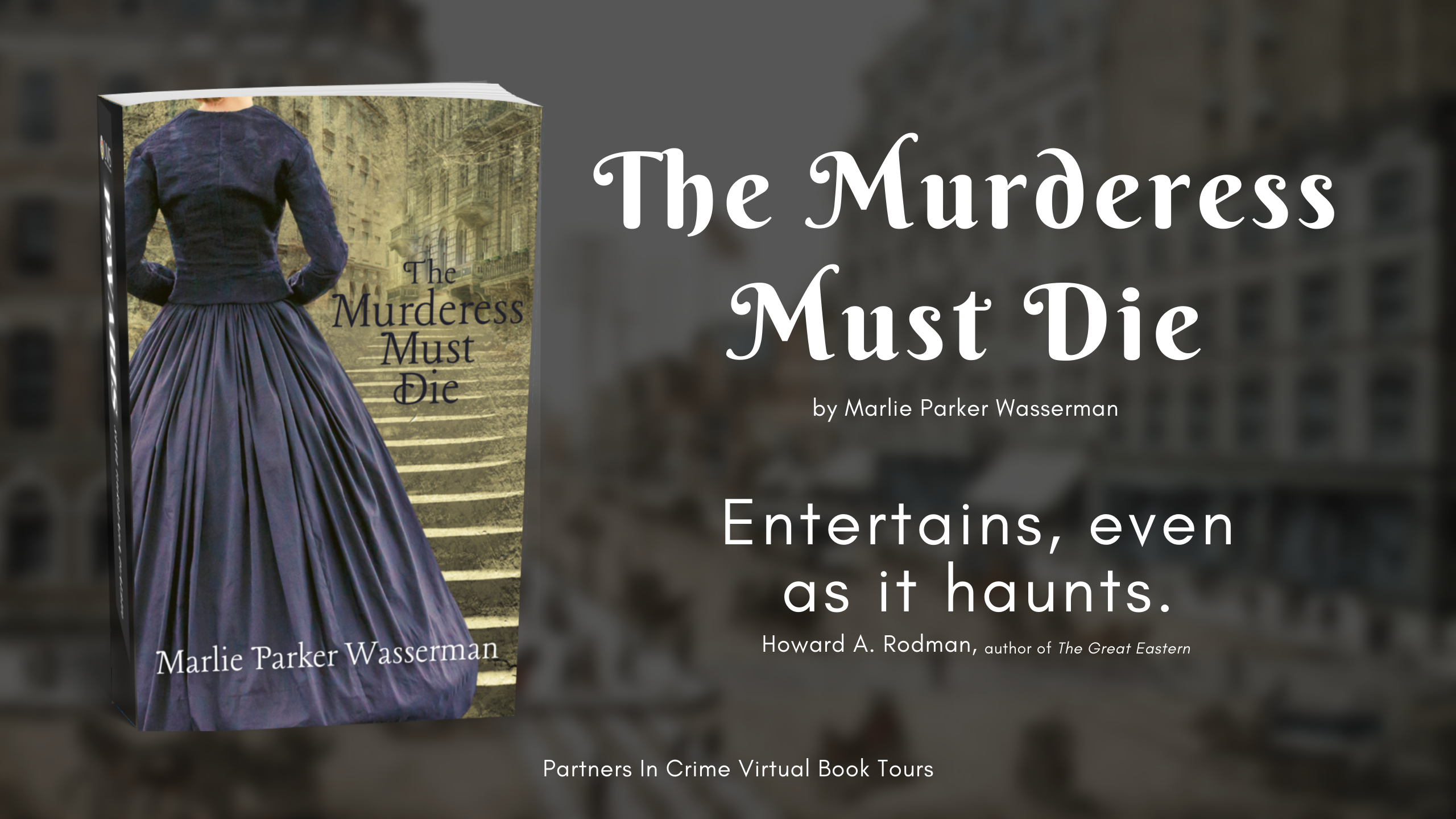

Publication Date: July 6, 2021

On a winter day in 1898, hundreds of spectators gather at a Brooklyn courthouse, scrambling for a view of the woman they label a murderess. Martha Place has been charged with throwing acid in her stepdaughter’s face, hitting her with an axe, suffocating her with a pillow, then trying to kill her husband with the same axe. The crowd will not know for another year that the alleged murderess becomes the first woman in the world to be executed in the electric chair. None of her eight lawyers can save her from a guilty verdict and the governor of New York, Theodore Roosevelt, refuses to grant her clemency.

On a winter day in 1898, hundreds of spectators gather at a Brooklyn courthouse, scrambling for a view of the woman they label a murderess. Martha Place has been charged with throwing acid in her stepdaughter’s face, hitting her with an axe, suffocating her with a pillow, then trying to kill her husband with the same axe. The crowd will not know for another year that the alleged murderess becomes the first woman in the world to be executed in the electric chair. None of her eight lawyers can save her from a guilty verdict and the governor of New York, Theodore Roosevelt, refuses to grant her clemency.

Was Martha Place a wicked stepmother, an abused wife, or an insane killer? Was her stepdaughter a tragic victim? Why would a well-dressed woman, living with an upstanding husband, in a respectable neighborhood, turn violent? Since the crime made the headlines, we have heard only from those who abused and condemned Martha Place.

Speaking from the grave she tells her own story, in her own words. Her memory of the crime is incomplete, but one of her lawyers fills in the gaps. At the juncture of true crime and fiction, The Murderess Must Die is based on an actual crime. What was reported, though, was only half the story.

A true crime story. But in this case, the crime resides in the punishment. Martha Place was the first woman to die in the electric chair: Sing Sing, March 20, 1899. In this gorgeously written narrative, told in the first-person by Martha and by those who played a part in her life, Marlie Parker Wasserman shows us the (appalling) facts of fin-de-siècle justice. More, she lets us into the mind of Martha Place, and finally, into the heart. Beautifully observed period detail and astute psychological acuity combine to tell us Martha’s story, at once dark and illuminating. The Murderess Must Die accomplishes that rare feat: it entertains, even as it haunts.

— Howard A. Rodman, author of The Great Eastern

The first woman to be executed by electric chair in 1899, Martha Place, speaks to us in Wasserman’s poignant debut novel. The narrative travels the course of Place’s life describing her desperation in a time when there were few opportunities for women to make a living. Tracing events before and after the murder of her step-daughter Ida, in lean, straightforward prose, it delivers a compelling feminist message: could an entirely male justice system possibly realize the frightful trauma of this woman’s life? This true-crime novel does more–it transcends the painful retelling of Place’s life to expand our conception of the death penalty. Although convicted of a heinous crime, Place’s personal tragedies and pitiful end are inextricably intertwined.

— Nev March, author of Edgar-nominated Murder in Old Bombay

The Murderess Must Die would be a fascinating read even without its central elements of crime and punishment. Marlie Parker Wasserman gets inside the heads of a wide cast of late nineteenth-century Americans and lets them tell their stories in their own words. It’s another world, both alien and similar to ours. You can almost hear the bells of the streetcars.

— Edward Zuckerman, author of Small Fortunes and The Day After World War Three, Emmy-winning writer-producer of Law & Order

This is by far the best book I have read in 2021! Based on a true story, I had never heard of Mattie Place prior to reading this book. I loved all of the varying voices telling in the exact same story. It was unique and fresh and so wonderfully deep. I had a very hard time putting the book down until I was finished!

It isn’t often that an author makes me feel for the murderess but I did. I connected deeply with all of the people in this book, and I do believe it will stay with me for a very long time.

This is a fictionalized version of the murder of Ida Place but it read as if the author Marlie Parker Wasserman was a bystander to the actual events. I very highly recommend this book.

— Jill, InkyReviews

This is a Rafflecopter giveaway hosted by Partners in Crime Virtual Book Tours for Marlie Parker Wasserman. There will be 1 winner of one (1) Amazon.com Gift Card (U.S. ONLY). The giveaway runs from August 16th until September 10, 2021. Void where prohibited.

Marlie Parker Wasserman writes historical crime fiction, after a career on the other side of the desk in publishing. The Murderess Must Die is her debut novel. She reviews regularly for The Historical Novel Review and is at work on a new novel about a mysterious and deadly 1899 fire in a luxury hotel in Manhattan.

Marlie Parker Wasserman writes historical crime fiction, after a career on the other side of the desk in publishing. The Murderess Must Die is her debut novel. She reviews regularly for The Historical Novel Review and is at work on a new novel about a mysterious and deadly 1899 fire in a luxury hotel in Manhattan.

Loved this guest post! Sounds like an interesting read.

Great cover BTW!

Right? I was intrigued from the get-go!