In July 2020, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition published a report and listed Boston as the third most gentrified city in the United States, after San Francisco and Denver. Shane Cleary, the former Boston cop and now PI for hire, lives in the South End during the 1970s. His neighborhood, rich with multiethnic diversity, underwent intense gentrification during the Aughts.

The thriving music and food scene, close to Boston’s Theatre District, were long gone by the 1960s. The South End fell into disrepair and acquired a notorious reputation as the city’s Skid Row, where sketchy bars outnumbered restaurants, and prostitution and drugs were rampant. When gentrification arrived in the name of erasing blight, long-term residents were pushed out because they couldn’t afford the rents. As of today, December 20, 2020, the average rent for a 1-bedroom apartment in Boston’s South End is $2,400 a month, and that is a 25% decrease compared to the previous year.

If anything remained of the South End’s storied diversity, it was the neighborhood’s large gay population, who have now become the primary owners of real estate and businesses. They are connected, moneyed, and their clientele is both white and privileged. Out with the Old and in with the New is not new in Boston, the City upon the Hill. As with most cities in America, people moved from the city to the suburbs as incomes and opportunities increased.

The weird thing about Boston is that, despite its history, physical appearance seemed last on the list of improvements. When Harvard student Jane Britton was murdered in her Cambridge apartment in 1969 and detectives scoured the Harvard campus for clues and suspects, they were shocked at the lack of safety measures and the state of disrepair in university housing. While Americans watched Cheers and Spenser: For Hire on their TVs, they wouldn’t know that the oldest park in the nation, The Boston Common, and the nearby Public Garden were (and continue to be) maintained by the Friends of the Public Garden, a private group founded by Henry Lee, because the city had done nothing to address the death of trees from Dutch Elm disease or vandalism to the numerous statues. Henry Lee and The Friends fought the Park Plaza Urban Renewal Plan for four decades in order to save public spaces.

In both Shane Cleary novels, Dirty Old Town and Symphony Road, there is the echo of urban renewal, or calls to rid the city of eyesores. Often, these efforts were nothing more than veiled attempts to seize land and profits. Boston’s notorious Combat Zone, a few blocks of sex shops and strip joints, managed to last until the 1990s. Other parts of the city have not been so lucky. Residents of Boston’s West End, home to Italians and Jews, were served summary eviction notices by city officials, and their neighborhood and Scollay Square were leveled in the early 60s to create the hideous Government Center. I strongly suggest that you listen to Leonard Nimoy’s recollections of the West End he knew on Youtube. So much history was lost, in the name of greed. The Gaiety Theatre, a destination for African American performers, was demolished because the Boston Landmark Commission determined it was not worth saving.

Symphony Road does reference one successful resistance to gentrification. Latinos, namely Puerto Ricans, in the South End faced the same fate as West Enders. Within months, they formed an activist committee, crafted a Request for Proposal, and hired construction companies. They proved the politicians wrong and embarrassed the committeemen for urban renewal, who said minorities didn’t have the means and wherewithal for urban planning. IBA, the activist group, had hired architects and built Villa Victoria, complete with modern housing and amenities for children, the elderly, and low-income families, under cost and on time.

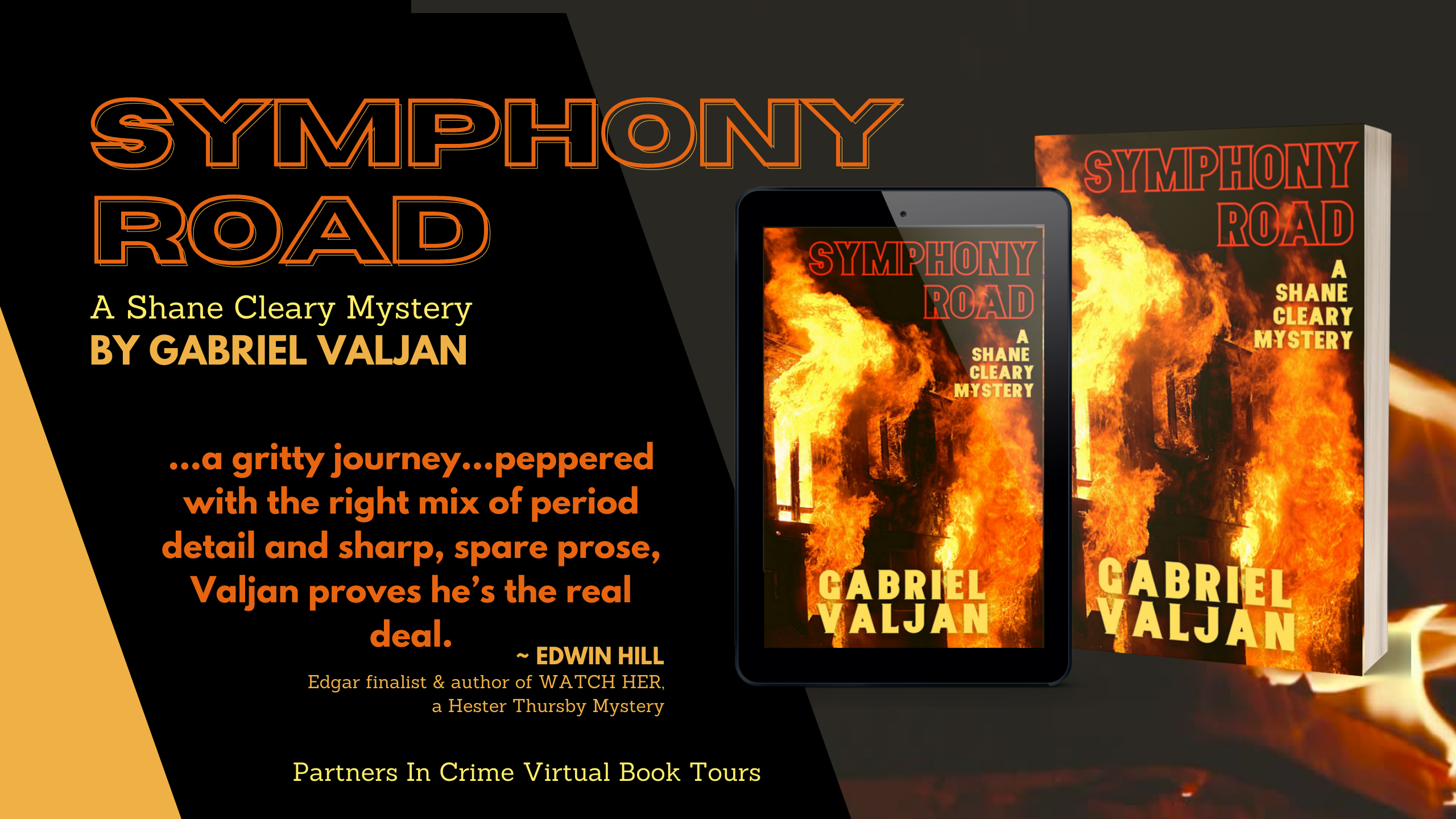

Shane Cleary Mystery: Book #2

Publication Date: January 15, 2021

Trouble comes in threes for Shane Cleary, a former police officer and now, a PI.

Arson. A Missing Person. A cold case.

Two of his clients whom he shouldn’t trust, he does, and the third, whom he should, he can’t.

Shane is up against crooked cops, a notorious slumlord and a mafia boss who want what they want, and then there’s the good guys who may or may not be what they seem.

“The second installment in this noir series takes us on a gritty journey through mid-seventies Boston, warts and all, and presents Shane Cleary with a complex arson case that proves to be much more than our PI expected. Peppered with the right mix of period detail and sharp, spare prose, Valjan proves he’s the real deal.” – Edwin Hill, Edgar finalist and author of Watch Her

“Ostracized former cop turned PI Shane Cleary navigates the mean streets of Boston’s seedy underbelly in Symphony Road. A brilliant follow up to Dirty Old Town, Valjan’s literary flair and dark humor are on full display.” – Bruce Robert Coffin, award-winning author of the Detective Byron Mysteries

“A private eye mystery steeped in atmosphere and attitude.” – Richie Narvaez, author of Noiryorican

Gabriel Valjan lives in Boston’s South End. He is the author of the Roma Series and Company Files (Winter Goose Publishing) and the Shane Cleary series (Level Best Books). His second Company File novel, The Naming Game, was a finalist for the Agatha Award for Best Historical Mystery and the Anthony Award for Best Paperback Original in 2020. Gabriel is a member of the Historical Novel Society, International Thriller Writer (ITW), and Sisters in Crime.

Gabriel Valjan lives in Boston’s South End. He is the author of the Roma Series and Company Files (Winter Goose Publishing) and the Shane Cleary series (Level Best Books). His second Company File novel, The Naming Game, was a finalist for the Agatha Award for Best Historical Mystery and the Anthony Award for Best Paperback Original in 2020. Gabriel is a member of the Historical Novel Society, International Thriller Writer (ITW), and Sisters in Crime.

Catch Up With Gabriel Valjan:

Blog Tour Organized By:

Living over the line in RI and visiting Boston quite a bit, I found this post quite interesting and it even taught me things I didn’t know. Thank you for sharing.