I was nine when I first encountered Christmas. I grew up in the Soviet Union, a communist country that had not only banished religion, but outlawed all religious trappings—even owning a bible could get you a stint in a GULAG (concentration camp).

I was nine when I first encountered Christmas. I grew up in the Soviet Union, a communist country that had not only banished religion, but outlawed all religious trappings—even owning a bible could get you a stint in a GULAG (concentration camp).

The closest my father came to a bible was a book called Biblical Fables, with a picture of Michelangelo’s Moses on the cover. He read the stories to me in secret, making it clear I was not to discuss the book with my friends.

When I turned eight, the government finally granted us exit visas, and we boarded a train to Austria, and from there, Italy, where we settled in the waterfront neighborhood of Ostia in Rome. There we waited for a country, any country, to grant us entry visas. For the five months we lived in Italy, we were stateless refugees, belonging nowhere.

And it was in Rome that I experienced my first Christmas. I had no idea what it was. I remember standing on an evening street with my father, shopfronts and homes decorated with fairy lights, a wispy snow falling, and everyone celebrating. I asked him what was going on, and he said he believed this was how Christians celebrated Christmas.

By then we had been to the Vatican and traveled on a bus tour through northern Italy, visiting every single church in our path. At no point had I connected the breathtakingly beautiful cathedrals, stained glass, mosaics, sculptures and frescoes to a belief system or even to a way of life. To me it was art and history—fascinating, gorgeous, otherworldly, and definitely not mundane. Not something a regular, modern person would practice.

After the Russian revolution, what had been a deeply religious country became militantly secular—from the top down. Priests were rounded up, executed, sent to labor camps. Churches were destroyed. But the Russian people could not uproot their traditions, superstitions, and their God, no matter how much they may have wanted a change. And thus, Christmas became New Year’s Eve.

Each Christmas tradition, minus any hint of Christ, was relocated to December 31st. From communal apartments to wooden huts in small villages, every family put up a fir tree. There were lights and pretty glass ornaments. And on top, a red star (what else?)

New Year’s Eve was when all the families got together, all the young people partied, all the children stayed up ‘till the wee hours. Feasts were cooked and gifts exchanged at midnight. Even the Kremlin offered a New Year’s celebration to Moscow’s children, or at least it did when I was a child. Somehow my parents procured a ticket for me and I spent one New Year’s inside the Kremlin, watching cartoons, and carefully saving the chocolate-filled goodie bag the ushers handed out.

We arrived at New York’s JFK Airport December 28th, with almost no cash, a few suitcases, our bedding and cookware bundled inside blankets tied with twine. Two organizations helped us find our footing, HIAS and NYANA*. Between them they found us temporary accommodations in, what I think was, a welfare hotel. The toilet didn’t work right, and snow drifted onto our beds from broken windows.

But my parents were determined we have a proper American New Year’s Eve, with gifts. About a week before we left Italy, thieves broke into our Ostia apartment, and stole our carefully hidden cash. The little we had when we landed in New York was a loan from one of the organizations.

On December 31st we went into a convenience store, and my father said we each could choose a small thing for ourselves. On the shelves, brightly colored packages of cookies, chocolates, lollipops tempted me. I’d never seen such things. I wanted each and every one of them. In the end, I settled on a bag of gum drops because they were the most colorful and the most unusual.

My mother, who had been missing Russian pastries and home-cooked pies, chose an Entenmann’s apple pie. But it was my father who injected a note of excitement into his choice because he wanted to try real American beer. Much like me, he picked the can with the most colorful label.

At midnight we cheered and hugged each other and opened our gifts. My parents had splurged and, in addition to my gum drops, had given me a magic marker (because I was always drawing) and a Mickey Mouse figurine. I was beside myself as I tore open my gum drop packet and put one in my mouth. Unusual, yes. Sweet, yes. Disappointing? The jury is still out.

My mother cut herself a chunk of apple pie and dug in.

“It’s not cooked,” she said.

“What?” we asked.

“It’s runny,” my mother said. Used to the solid, firmly baked Russian apple cakes, she didn’t know what to make of the gooey, cinnamon flecked bits of softened apple and dough.

We looked at my father as he poured himself his first taste of genuine American beer. He took a deep pull. He set it down and looked at it. He sniffed it. He grunted. But since we paid for it, he finished it. What my father had gotten himself was a lovely can of genuine American root beer. For the rest of his life he maintained root beer was a laxative and never touched it again.

Within a month we were ensconced in an apartment in Queens and I started school. I only knew three English words despite my parents having paid for an English tutor back in Moscow. For no good reason, those words were “table”, “chair”, and “candlestick”. Very quickly, I began to absorb not just my new language, but my new American culture.

A year later we unpacked our plastic tree, which, unbelievably, had made its way to our apartment from Moscow over six long months on a ship. Even more unbelievably, our glass ornaments survived the trip, and we hung every single one on the tree and plugged it in. New Year’s!

But by now I was ten and I knew something about something. I knew American children got their gifts on December 25th, and thus began my years’ long campaign to move New Year’s back to Christmas.

What made this crusade even more confusing to my parents was that we were Jews. Being Jews was the number one reason we left the Soviet Union in the first place. Russia was, and to a degree still is, a vehemently anti-Semitic country. Our old passports stated our nationality as “Jewish”, not “Russian.” My father was told to forget even trying to apply to medical school—they’d reached their Jew quota for the year. At my tender age I’d already been called every slur by other children, and our entire extended family knew that if we didn’t leave, my father would be arrested for anti-government agitation (if not for owning a book of bible stories).

Christmas roamed in our household. We’d celebrate on the 28th (the anniversary of us arriving in America), on the 26th (don’t know why), and finally, FINALLY, on the 25th. By the time I entered my teenage years, the date depended on who I was dating. If an American, then the 25th. If not, then it was a pizza and a movie on the 25th and a big blowout on the 31st.

When I met the man who is now my husband, Christmas at last crystalized in my life. He bought me a Tom Waits album (not because he liked Tom Waits, but because I did), and my first pair of Doc Martens. He brought me to his family’s house, and for the first time I was surrounded by lights, Christmas music, children in velvet outfits, gifts, drinks, gingerbread houses.

Now we celebrate everything, Christmas, Hannukah, New Year’s Eve. And mixed in the middle of all that is December 28th, the date I came to America, but also our wedding anniversary. Having started with one winter holiday, I now juggle four, and the last week of December is full of light, food, friends, and gifts.

I still have many of the glass ornaments that voyaged by ship from Moscow to Queens, then Long Island, and now the Hudson Valley. Every year my son hangs them with me next to ones we inherited from his American great-grandmother and the lopsided ceramic trees and snowmen he made as a Cub Scout.

I still have many of the glass ornaments that voyaged by ship from Moscow to Queens, then Long Island, and now the Hudson Valley. Every year my son hangs them with me next to ones we inherited from his American great-grandmother and the lopsided ceramic trees and snowmen he made as a Cub Scout.

Christmas means many things to different people, but to me it means America, in all its dazzling, generous, consumerist glory.

* HIAS is an organization that still helps refugees of every creed. If this is a cause special to your heart, take a look at their website. NYANA closed its doors in 2008 after having helped roughly 500,000 refugees from all over the world settle in New York.

[rafflepress id=”9″]

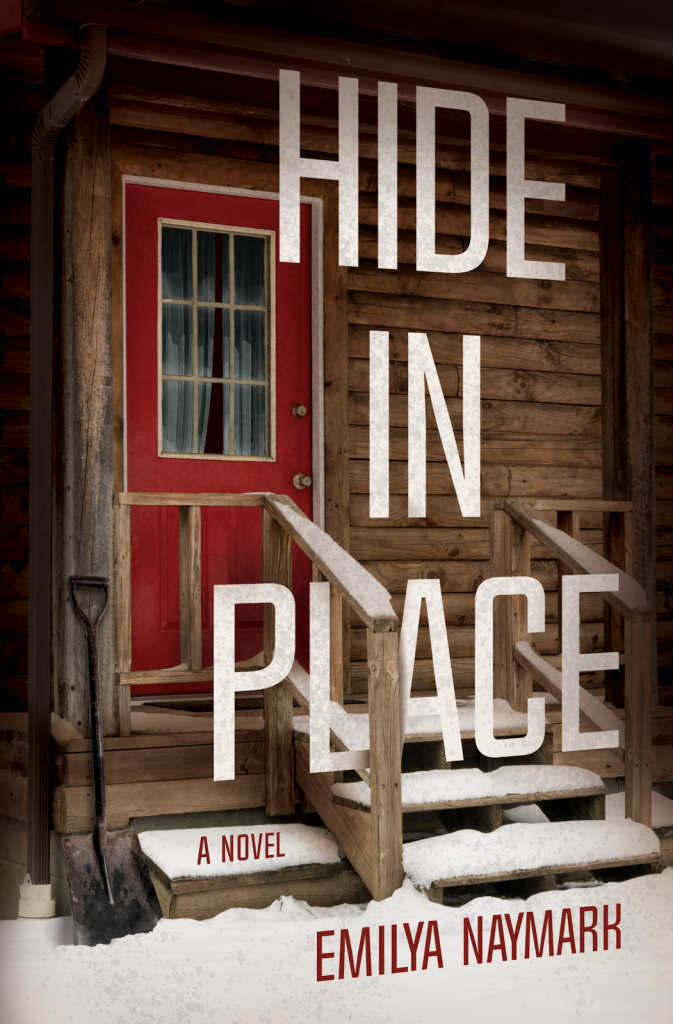

When NYPD undercover cop Laney Bird’s cover is blown in a racketeering case against the Russian mob, she flees the city with her troubled son, Alfie. Now, three years later, she’s found the perfect haven in Sylvan, a charming town in upstate New York. But then the unthinkable happens: her boy vanishes.

When NYPD undercover cop Laney Bird’s cover is blown in a racketeering case against the Russian mob, she flees the city with her troubled son, Alfie. Now, three years later, she’s found the perfect haven in Sylvan, a charming town in upstate New York. But then the unthinkable happens: her boy vanishes.

Local law enforcement dismisses the thirteen-year-old as a runaway, but Laney knows better. Alfie would never abandon his special routines and the sanctuary of their home. Could he have been kidnapped—or worse? As a February snowstorm rips through the region, Laney is forced to launch her own investigation, using every trick she learned in her years undercover.

As she digs deeper into the disappearance, Laney learns that Alfie and a friend had been meeting with an older man who himself vanished, but not before leaving a corpse in his garage. With dawning horror, Laney discovers that the man was a confidential informant from a high-profile case she had handled in the past. Although he had never known her real identity, he knows it now. Which means several other enemies do, too. Time is running out, and as Laney’s search for her son grows more desperate, everything depends on how good a detective she really is—badge or no.

Emilya Naymark was born in a country that no longer exists, escaped with her parents, lived in Italy for a bit, and ended up in New York, which promptly became a love and a muse.

Her debut novel “Hide In Place”, is out February 9, 2021 from Crooked Lane Books.

Her short stories appear in the Harper Collins anthology A Stranger Comes to Town, Secrets in the Water, After Midnight: Tales from the Graveyard Shift, River River Journal, Snowbound: Best New England Crime Stories 2017, and 1+30: THE BEST OF MYSTORY.

She has a degree in fine art, and her artworks have been published in numerous magazines and books.

When not writing, Emilya works as a visual artist and reads massive quantities of psychological thrillers, suspense, and crime fiction. She lives in the Hudson Valley with her family.