The first author to kick off our “Holiday Memories” is the USA Today bestselling author, Karen Odden! I’m elated to have Karen as our first author. I first discovered Karen’s books a few years ago and absolutely fell in love with her writing. Her attention to detail and ability to paint a visual picture kept me enthralled through each and every page of her books.

The first author to kick off our “Holiday Memories” is the USA Today bestselling author, Karen Odden! I’m elated to have Karen as our first author. I first discovered Karen’s books a few years ago and absolutely fell in love with her writing. Her attention to detail and ability to paint a visual picture kept me enthralled through each and every page of her books.

I invite you to take a taste of Karen’s outstanding writing as you learn more about how Christmas become what it is today.

Many elements of British life—including railways, manufacturing, the postal service, medicine, children’s schools, and diet—changed shape over Queen Victoria’s long reign, from 1837 to 1901, gradually taking on the forms we recognize today. One aspect that changed almost completely was Christmas. When eighteen-year-old Victoria took the throne, Christmas was barely celebrated as a holiday. Indeed, it was a workday for many. Gift-giving, if it was done at all, was done at New Year’s, and most of the elements we now think of as inseparable from Christmas—the decorated tree, gift exchanges, Santa Claus, and holiday cards—were non-existent in Britain.

However, by the end of Victoria’s reign, Christmas was the largest annual celebration—but only in England and Wales. Interesting fact: despite having joined the United Kingdom in 1707, Scotland held itself aloof from the Christmas traditions that swept Britain in the nineteenth century. Instead, Scots celebrated Hogmanay.  This celebration of the winter solstice was brought to Scotland by the invading Vikings in the 8th and 9th centuries. Later, it was marked at the New Year by customs such as “first-footing,” in which someone (preferably a dark-haired male) is the first to cross a house’s threshold on New Year’s Day, with gifts that bring good fortune for the coming year. Christmas, viewed as a Popish Catholic feast, was banned in Scotland from the 17th century until the 1950s, so Scots did not celebrate Christmas the way England and Wales did until around 1960.

This celebration of the winter solstice was brought to Scotland by the invading Vikings in the 8th and 9th centuries. Later, it was marked at the New Year by customs such as “first-footing,” in which someone (preferably a dark-haired male) is the first to cross a house’s threshold on New Year’s Day, with gifts that bring good fortune for the coming year. Christmas, viewed as a Popish Catholic feast, was banned in Scotland from the 17th century until the 1950s, so Scots did not celebrate Christmas the way England and Wales did until around 1960.

For many scholars of religion, the history of Christmas begins in the 4th century. The Bible does not provide an exact date for Jesus’s birth, but perhaps drawing on the enthusiasm for traditional pagan celebrations around the winter solstice (December 21), Pope Julius I named it as December 25. First called the “Feast of the Nativity,” it spread to England by the end of the 6th century and through most of the rest of Europe by the 8th where it became an established tradition. During a period of puritanism in the 17th century, in America as well as England and Wales, Christmas was outlawed briefly as a “decadent” holiday. Although Christmas reemerged as a holiday in England by the 1680s, it wasn’t until the first half of the 19th century that writers on both sides of the Atlantic played a significant role in bringing modern notions of Christmas, popularizing it as a holiday that celebrates family, charity, and love.

In America in 1819, best-selling author Washington Irving wrote The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, gent., a series of stories about the celebration of Christmas in an English manor house. Ironically, people who lived in English manor houses didn’t celebrate Christmas in the way he depicts it, but Irving’s sketches feature a squire who invited the peasants into his home for the holiday—a theme of generosity and good will toward those who are less fortunate, which Charles Dickens would later adopt and popularize more than twenty years later, on the other side of the Atlantic.

In America in 1819, best-selling author Washington Irving wrote The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, gent., a series of stories about the celebration of Christmas in an English manor house. Ironically, people who lived in English manor houses didn’t celebrate Christmas in the way he depicts it, but Irving’s sketches feature a squire who invited the peasants into his home for the holiday—a theme of generosity and good will toward those who are less fortunate, which Charles Dickens would later adopt and popularize more than twenty years later, on the other side of the Atlantic.

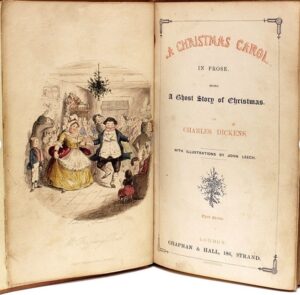

A Christmas Carol, written by Dickens in 1843, is perhaps the ultimate English Christmas story, celebrating kindness, generosity, and nonreligious spirituality.

But even so, there is no mention of a tree or Santa Claus or an exchange of gifts or cards in it. Indeed, the tale was not intended to celebrate the holiday; it was aimed at social reform during the country’s recession, also known as the “Hungry 40s.” Having witnessed the effects of brutal poverty and starvation in Manchester, and full of indignation, Dickens wrote the novella in six weeks, to spur (or shame) the wealthy to give generously to the poor. The book was published on December 19, in time for Christmas and reprinted multiple times, as it was an immediate, overwhelming success.

But even so, there is no mention of a tree or Santa Claus or an exchange of gifts or cards in it. Indeed, the tale was not intended to celebrate the holiday; it was aimed at social reform during the country’s recession, also known as the “Hungry 40s.” Having witnessed the effects of brutal poverty and starvation in Manchester, and full of indignation, Dickens wrote the novella in six weeks, to spur (or shame) the wealthy to give generously to the poor. The book was published on December 19, in time for Christmas and reprinted multiple times, as it was an immediate, overwhelming success.

Christmas in England and Wales also evolved in part as a consequence of the industrial revolution, which helped to create a middle-class—merchants, factory owners, manufacturers, railway and shipping magnates, and so on—with disposable income. They could spend their money on many of the new products manufactured in these factories, including toys, games, dolls, textiles, decorative objects, and so on—which all became more affordable, as they were no longer painstakingly made by hand.  So Christmas was yet another aspect of society that altered in part as a result of the industrialization and mechanization beginning in the 1830s. By mid-century, the steam-engine driven trains (begun in the 1830s with the inaugural run of the Liverpool-Manchester Railway) allowed people who had moved to cities to find work to return to the country to spend Christmas with their families.

So Christmas was yet another aspect of society that altered in part as a result of the industrialization and mechanization beginning in the 1830s. By mid-century, the steam-engine driven trains (begun in the 1830s with the inaugural run of the Liverpool-Manchester Railway) allowed people who had moved to cities to find work to return to the country to spend Christmas with their families.

Did you know it was Queen Victoria’s German-born husband Prince Albert who brought the tradition of Christmas trees to England? He brought the first fir tree to Windsor Castle in 1841, and in 1848 the Illustrated London News popularized the idea of putting a decorated tree inside the home for the middle classes by publishing an image of Queen Victoria, the Prince Consort, and several of their children standing around the tree in familial bliss.

By mid-century, the tree was often decorated with homemade ornaments and homemade sweets, tied on by ribbons. The industrial revolution later contributed machine-made glass, metal, and ceramic ornaments to the handmade ones of wire and paperboard. The unusual Sebnitz ornaments were a cottage industry in Germany beginning in the 1880s. Trees were also decorated with “lametta”—thin wire or foil metallic garland, which we’d now call tinsel. A Nuremburg tinsel angel often topped the tree.

By mid-century, the tree was often decorated with homemade ornaments and homemade sweets, tied on by ribbons. The industrial revolution later contributed machine-made glass, metal, and ceramic ornaments to the handmade ones of wire and paperboard. The unusual Sebnitz ornaments were a cottage industry in Germany beginning in the 1880s. Trees were also decorated with “lametta”—thin wire or foil metallic garland, which we’d now call tinsel. A Nuremburg tinsel angel often topped the tree.

Christmas Crackers were invented in 1846. Tom Smith, a sweet-maker in London, had seen the “bon bons” in France, which were sugar-coated almonds twisted up in decorative bits of paper. He had the idea of twisting paper around small candies, gifts or jokes. In the 1860s, he perfected the explosive “bang” of the cracker and, filled them with small toys such as whistles or miniature dolls or other gifts, they became a standard part of the Christmas celebration.

Christmas Crackers were invented in 1846. Tom Smith, a sweet-maker in London, had seen the “bon bons” in France, which were sugar-coated almonds twisted up in decorative bits of paper. He had the idea of twisting paper around small candies, gifts or jokes. In the 1860s, he perfected the explosive “bang” of the cracker and, filled them with small toys such as whistles or miniature dolls or other gifts, they became a standard part of the Christmas celebration.

Christmas cards came into being partly as a result of a change in the postal service. Until 1840, postage was paid by recipients rather than the senders, and the price was calculated by the number of miles a letter traveled. But in 1840, Rowland Hall reformed the postal service, switching it to a sender-pay system, with a flat rate for a letter sent anywhere in Britain, and the Penny Post was born. This made the cost of sending a card or letter affordable for many. (In 1870, a further reduction meant newspapers and postcards could be sent for a half-penny.) In 1843, Sir Henry Cole (later the director of the Victoria & Albert Museum) commissioned the artist J. C. Horsley to design a card with a festive scene, some of which he used himself and the remainder of which he sold.  He printed 1,000 at 1 shilling each (about $9,000 today), which was very expensive, but with the industrial revolution, improvements in production made them affordable. Queen Victoria sent hundreds of cards out each year. In 1880, 11 million cards were printed and sent.

He printed 1,000 at 1 shilling each (about $9,000 today), which was very expensive, but with the industrial revolution, improvements in production made them affordable. Queen Victoria sent hundreds of cards out each year. In 1880, 11 million cards were printed and sent.

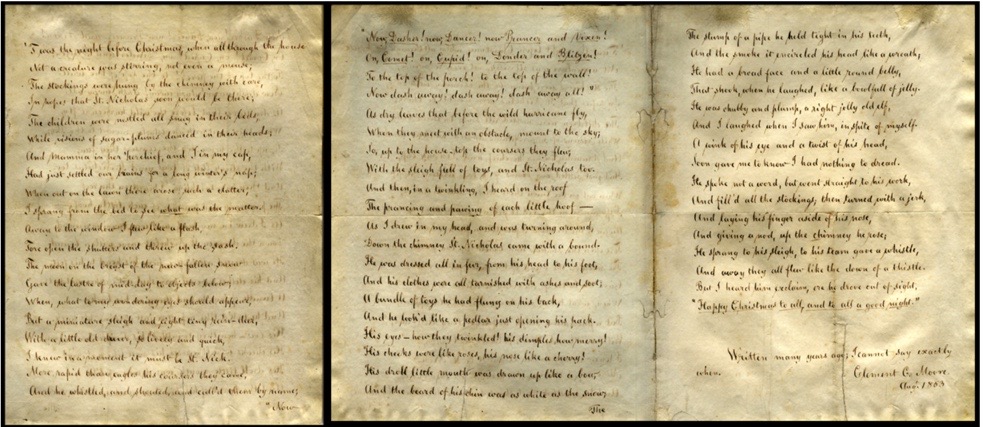

Our version of Santa Claus evolved from to two different European traditions: “Father Christmas” and “Santa Claus.” “Father Christmas” originated in an old medieval festival, and he was dressed in green to signify that spring would return. “Santa Claus” finds its origins in a Turkish monk named St. Nicholas (circa 280 A.D.) who gave away his inherited wealth and helped the poor and the sick. This figure morphed into Holland’s “Sinter Klaas,” whom the Dutch settlers brought with them to America in the 17th century, where they celebrated the anniversary of his death. In 1822, an American Episcopal minister named Clement Clarke Moore drew upon this tradition when he wrote a Christmas poem called “An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas,” now known more popularly as “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas.”

Our version of Santa Claus evolved from to two different European traditions: “Father Christmas” and “Santa Claus.” “Father Christmas” originated in an old medieval festival, and he was dressed in green to signify that spring would return. “Santa Claus” finds its origins in a Turkish monk named St. Nicholas (circa 280 A.D.) who gave away his inherited wealth and helped the poor and the sick. This figure morphed into Holland’s “Sinter Klaas,” whom the Dutch settlers brought with them to America in the 17th century, where they celebrated the anniversary of his death. In 1822, an American Episcopal minister named Clement Clarke Moore drew upon this tradition when he wrote a Christmas poem called “An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas,” now known more popularly as “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas.”

In it, St. Nick appears as a benevolent, jolly man, in a red suit, with a sleigh laden with gifts and eight reindeer. (Our favorite reindeer, the red-nosed Rudolph, appears in 1939, courtesy of the Montgomery Ward department stores, who wanted to save money on coloring books and printed their own that year, featuring Rudolph. The song was later popularized by Gene Autry in 1949.) But this version of Santa Claus, as a merry gentleman riding behind reindeer, did not cross the Atlantic to England until the 1870s.

One last note: while Boxing Day, celebrated on December 26, is separate from Christmas Day, it is a long-standing element of the holiday tradition in England. It has nothing to do with the pugilistic sport. After working on Christmas Day, servants were given the day off to spend with their families, and it is traditionally a day when money and gifts were distributed in boxes to servants, delivery people, and the poor.  This spirit of generosity, celebrated by writers on both sides of the Atlantic over 150 years ago, remains a hallmark of Christmas today.

This spirit of generosity, celebrated by writers on both sides of the Atlantic over 150 years ago, remains a hallmark of Christmas today.

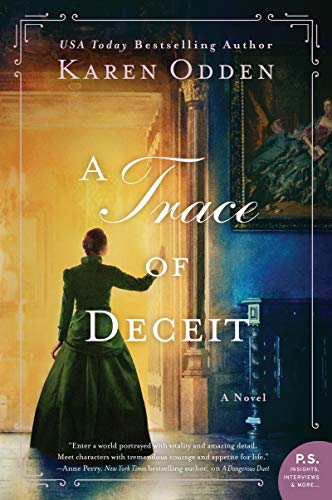

Karen is giving away one paperback copy of A Trace of Deceit! To enter, please use the form below.

The giveaway is open to US residents only and ends at midnight January 1st. You must be 18 or older to enter.

[rafflepress id=”3″]

A young woman painter digs beneath the veneer of Victorian London’s art world to learn the truth behind her brother’s murder.

A young woman painter digs beneath the veneer of Victorian London’s art world to learn the truth behind her brother’s murder.

“Edwin is dead.” This is what Scotland Yard Inspector Matthew Hallam tells Annabel Rowe when she discovers him searching her brother’s flat for clues. Annabel is devastated but not wholly surprised, given Edwin’s history as a swindler and convicted art forger.

Recently released from prison, Edwin swore he’d reformed and wanted to repair his broken relationship with her. Annabel wants desperately to believe him, but when she discovers that a priceless French painting is missing from his studio, she wonders if he had lied to her yet again, or if—despite Edwin’s best efforts—his old life had come back to haunt him.

Determined to know the truth, Annabel convinces Matthew that as a painter at the prestigious Slade School of Art and Edwin’s only family, she is crucial to his investigation. Together they trace a path of deceit and villainy that reaches far beyond the elegant rooms of the auction house, into an underworld of treachery, heartbreak, and secrets someone will kill to keep.

“Odden’s third effort injects a refreshing level of complexity, both in character development and plotting, into what one typically expects to find in historical cozies. This will appeal to fans of Victorian mysteries, as well as those interested in art history.” -Booklist (starred review)

“Odden keenly evokes the physical as well as cultural milieu of Victorian England, and peoples her setting with fully realized and intriguing characters. This book will delight readers who like their mysteries cloaked in well-researched history.” – Publishers Weekly

“…this thrilling, action-packed story [is] an absolute delight to read.” – Historical Novel Society

“Odden’s literary brushstrokes vividly portray the misogyny and gender bias experienced by women in Victorian society, especially a woman battling to exercise her artistic talent. ” -Washington Independent Review of Books

“Fans of Anne Perry, Deanna Rayborn, and Tasha Alexander will root for Karen Odden’s newest heroine, Annabel Rowe—aspiring painter and now amateur sleuth—investigating the murder of her art forger brother. The novel’s a delightful mix of mystery, history, and romance, served with a delicious helping of lush period detail, while chemistry between Annabel and the investigating Scotland Yard detective add spice to the adventure.” – Susan Elia MacNeal, New York Times bestselling author of the Maggie Hope series

“A darkly thrilling story filled with suspense and secrets, a courageous heroine, an edgy climax, and an atmospheric setting that perfectly captures the underbelly of London’s art world in the Victorian era. A Trace of Deceit is an absolute winner!” – Stefanie Pintoff, Edgar Award winning author.

Karen Odden received her Ph.D. in English literature from New York University, writing her dissertation on Victorian literature and culture. While teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, she contributed essays to books and journals, including Studies in the Novel, the Journal of Victorian Culture, and Victorian Crime, Madness, and Sensation. She has written introductions for Barnes and Noble editions of books by Dickens and Trollope; and she edited for the academic journal Victorian Literature and Culture. She freely admits she might be more at home in nineteenth-century London than today, especially when she tries to do anything complicated on her iPhone. Her first novel, A Lady in the Smoke, was a USA Today bestseller and won the New Mexico-Arizona 2016 Book Award for e-Book Fiction. Her second novel, A Dangerous Duet, about a young pianist who stumbles on a crime ring while playing in a Soho music hall in 1870s London, won the New Mexico-Arizona 2019 Book Award for Best Historical Fiction. A Trace of Deceit, set in the 1870s London art world, is her third novel. A member of Mystery Writers of America and Sisters in Crime, Karen resides in Arizona with her family and a ridiculously cute rescue beagle named Rosy.

Karen Odden received her Ph.D. in English literature from New York University, writing her dissertation on Victorian literature and culture. While teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, she contributed essays to books and journals, including Studies in the Novel, the Journal of Victorian Culture, and Victorian Crime, Madness, and Sensation. She has written introductions for Barnes and Noble editions of books by Dickens and Trollope; and she edited for the academic journal Victorian Literature and Culture. She freely admits she might be more at home in nineteenth-century London than today, especially when she tries to do anything complicated on her iPhone. Her first novel, A Lady in the Smoke, was a USA Today bestseller and won the New Mexico-Arizona 2016 Book Award for e-Book Fiction. Her second novel, A Dangerous Duet, about a young pianist who stumbles on a crime ring while playing in a Soho music hall in 1870s London, won the New Mexico-Arizona 2019 Book Award for Best Historical Fiction. A Trace of Deceit, set in the 1870s London art world, is her third novel. A member of Mystery Writers of America and Sisters in Crime, Karen resides in Arizona with her family and a ridiculously cute rescue beagle named Rosy.

Thank you so much for such a comprehensive post, Karen! This is spectacular!

I agree. This was amazing. Really interesting, and now I want to go off and do more research on Christmas history. Your book sounds amazing too!

Karen’s book is SO good! Well, all of them are! When I grow up, I want to be a writer like Karen. =)

Thank you for letting me share my enthusiasm for the Victorian era!! Those 64 years were just amazing … so many changes in so many aspects of life.